Global Ground

Reference: https://www.globalgroundmedia.com/2019/08/23/the-problems-with-progress/

In Asia, 92 percent of the continent’s population, around four billion people, breathe air that the World Health Organization (WHO) considers unsafe. The most dangerous pollutant, PM2.5, is ambient fine Particulate Matter with the ability to lodge deep in the lungs and enter the bloodstream. PM2.5 regularly reaches unhealthy levels in Asian cities from Delhi to Beijing and Chiang Mai. Ground-level ozone, the second-most detrimental pollutant to human health, also lingers on roadsides in megacities from Seoul to Hong Kong. Mobile apps and sites that monitor air quality often give warnings in the form of mask icons or “avoid outdoor exertion” on the worst days.

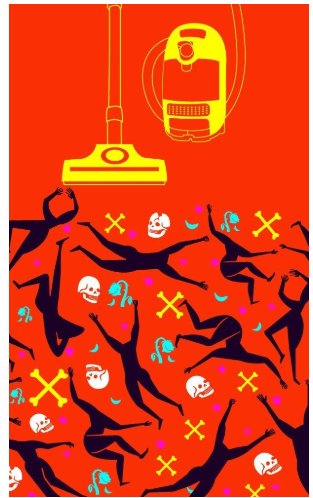

There are many solutions to these problems, and awareness of the issue is growing. From art installations that filter air in Beijing, to India’s immense solar fields and villagers in rural Thailand learning alternatives to crop burning, progress is in the air. However, this may not match the seriousness of the problem, and remedies thus far haven’t reached a global scale.

Now that widespread research, reporting, and outreach work by groups like the United Nations (UN) and the WHO has permeated nearly every corner of the globe, ignorance is no longer the norm. According to Bert Fabian, head of the UN Environment’s Air Quality and Mobility Unit Asia-Pacific, legitimate excuses for neglecting environmental responsibility are increasingly rare.

“I don’t think it should be an excuse now that if the country is still in a low stage of economic development that they do not have to set goals,” he says. “Myanmar can say, ‘we will adopt these standards in three years’, but at least it’s there and the private sector can start to prepare for the change.”

Governments across Asia are under increasing pressure to take action as the evidence of negative health effects mounts. Estimates by the WHO and the World Bank show that over a billion people are affected by respiratory diseases and over four million deaths are attributable to ambient air pollution each year. The majority of these deaths are in Asian countries with low median household incomes. Nearly half occur in India and China, where over one billion people breathe high levels of particulate matter and chemicals spewed by factories, power plants and vehicles.

In their 2017 global impact report, the WHO-affiliated Forum of International Respiratory Diseases (FIRD) states that “the control, prevention and cure of respiratory diseases are among the most cost-effective health interventions available – a ‘best-buy’ in the view of the WHO. Investment in respiratory health will pay manifold dividends in longevity, healthy living days and national economies.”

On one hand, globalisation may increase accountability and solution-sharing in this field, but on the other, it is at the heart of the problem. In a world where goods made in China are transported to the United States, food grown in Australia is eaten in Hong Kong, and waste created in the US is shipped back to Asia to be recycled — the lines of responsibility are blurred.

The air we breathe is no exception. Dust that originates in the deserts of western China is inhaled by city dwellers in Seoul, while the pollution of Indian cities darkens snow in the Nepalese Himalayas with black carbon — leading to premature snowmelt that sends a new set of problems downstream.

SOUTH KOREA: PURIFIERS, MASKS, APPS, AND ANXIETY

In South Korea, where nearly 50 percent of airborne particulates can be traced to China, many turn to personal preventative measures like masks and air purifiers, which bring some immediate physical and mental relief.

However, domestic pollution sources are still a significant concern. South Korea’s air is the second-most polluted of all Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member countries, preceded by Chile. The country’s steel and cement industries, along with coal-fired power plants, are South Korea’s main domestic sources of pollution.

Research indicates that the average person in South Korea is highly concerned with air pollution. In a 2017 study by the government-affiliated Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, South Koreans ranked air pollution as their top concern — above their volatile, nuclear-armed northern neighbour or an aging population.

In a more recent 2018 survey by the Ministry of Environment, 97 percent of respondents said they had been negatively affected by air pollution; while 60 percent identified it as a “serious” problem and another 30 percent as an “extremely serious” problem.

Derek Fichtner, a university professor who moved to South Korea from the United States in 2002, started a blog and Facebook group called Clean Air Korea to facilitate solution-minded conversations about local air pollution. The group now has over 3,200 members and logs an average of 10 posts per day that range from do-it-yourself (DIY) air filter advice to questions about mask fits and air quality apps.

Fichtner became interested in opening a dialogue on the topic after multiple early attempts to protect himself from airborne pollutants backfired. Upon moving to Seoul, he bought an ionizing air purifier, which he says were very popular at the time. When he ended up with pneumonia a few months later, Fichtner learned of the negative effects of ionizing air purifiers. The machines are known to emit ozone gas, which can cause a number of problems, including throat irritation, coughing, chest pain, shortness of breath, and increased risk of respiratory infections like pneumonia.

In 2011, Fichtner and his wife bought another popular home appliance meant to improve indoor air, a humidifier that dispersed chemicals meant to kill mold. This time, it wasn’t long before his wife became violently sick. “She coughed a lot, so much that she cracked her rib,” recalls Fichtner. This time, he discovered that the chemicals in their machine were being linked to respiratory sickness across South Korea, including around 100 fatalities.

“Over the years, in the process of trying to make my air cleaner, I caused it to get worse and made myself more sick and my family more sick” says Fichtner.

Properly outfitting the average home in South Korea with high-quality air filtration systems can cost around USD1,000, according to Fichtner and the Clean Air Korea Facebook group. As a technology professor, he has shared DIY filter building videos using materials which cost around US$ 100 with the group.

HONG KONG’S APPROACH: PROGRESSIVELY PRACTICAL, OR PLAYING IT SAFE?

Elsewhere, awareness and understanding of air quality is not as strong as in Korea. For example, it is relatively low in Hong Kong compared to other high-income Asian cities like Seoul or Shanghai. In a 2018 World Green Organisation survey of 500 Hong Kong residents, 75 percent said that they considered air pollution a problem, but only 13 percent said that they would wear masks or use indoor air purifiers on polluted days.

Air quality varies tremendously in Hong Hong. A week that begins with sunshine and blue skies often ends with an impenetrable grey haze that hangs heavy over the city. On the most polluted days, not one reading from the territory’s 13 air quality meters, from the verdant Sai Kung Peninsula to the wealthy Mid-levels district, stays below the cautionary orange or red levels, signifying high levels of PM2.5 and ground-level ozone.

This variation is a point of contention for some. Patrick Fung, CEO of Hong Kong NGO Clean Air Network (CAN), says it helps the government consign responsibility, attributing sudden spikes in PM2.5 to “uncontrollable forces” like highly changeable weather and increased factory output over the border in mainland China.

Fung says that, for years, local government has used high regional air pollution as an excuse for unambitious targets that resemble predictions more than a call to action. Unsatisfied with the Environmental Protection Department’s most recent targets for PM2.5, Fung wants to see more far-reaching goals that will bring Hong Kong up to WHO standards sooner than later. “Why not allocate more resources, more political will, and the muscle we need to force that to happen?” asks Fung.

One local solution that seems to be on track is the tightening of standards for shipping vessels in Hong Kong waters. Despite the popular belief that the majority of Hong Kong’s pollution drifts over the border from southern China, the shipping industry is the city’s top source of pollution. Kwai Chung Port, a 15-minute bus ride from downtown, is the fifth-busiest port in the world, servicing over 300 cargo ships per week. Nearby Shenzhen Port is the third-busiest in the world.

The Hong Kong government estimates that the 2015 requirement for all ships to switch to low-sulphur fuel while at berth cut shipping emissions by 30 to 50 percent within the same year.

From 2014 to 2018, sulphur dioxide amounts dropped by 45 percent, while nitrogen dioxide and PM2.5 levels decreased by approximately 20 percent.

Following the success of the 2015 berthing regulation, in early 2019 the government enacted the more stringent “Fuel For Vessels” regulation requiring all seafaring vessels to use low-sulphur fuel or liquefied natural gas while operating in Hong Kong waters.

Hong Kong’s practical approach has produced favourable results at times, but Fung says that until the city enforces more difficult schemes, like implementing electronic road pricing to address its pervasive ozone problem, pollutants will continue to seriously affect the population.

INDIA: ADDRESSING THE EMERGENCY FROM ALL ANGLES

As a nation, India is seriously investing in solving its severe air pollution problems. The government predicts environmental spending will reach US$ 2.5 trillion by 2030 in order to reach their Paris Climate Agreement goals, many of which directly address air pollution.

The responses and solutions to the problem of air pollution vary widely throughout India, from installing vast solar fields and fighting for green space in Mumbai, to restricting driving based on even and odd license plate numbers and banning all single-use plastics in the nation’s capital.

In 2018, a study by Greenpeace and Air Visual reported that seven of the world’s ten most-polluted cities were in India. Delhi, India’s most populous city, home to over 20 million people, recorded an “unhealthy” annual PM2.5 average of 113.5 micrograms per cubic meter. Under 25 micrograms per cubic meter is widely considered safe.

Though the current situation may seem dire, Indian officials are setting ambitious goals, many of which they are on track to achieve.

Approximately 50 percent of India’s population is under 25, which some policy experts interpret positively as a population “open to change,” The areas left behind by recent decades of rapid development are often the most fertile ground for implementing sustainable infrastructure.

The Center for Environmental Research and Education (CERE), a nonprofit based in Mumbai, seizes opportunities in these spaces, installing solar systems on school roofs and starting urban afforestation projects in cities where real estate developers have uprooted thousands of trees.

Dr. Rashneh Pardiwala, the ecologist who runs CERE, says that the rural towns they outfit with solar panels usually have no pre-existing power infrastructure. “It is a lot simpler when the question is not, ‘do we want to switch to solar?’ but rather ‘do we want electricity?” she says.

With approximately 300 days of sun per year, India is fully embracing solar power as an antidote to problems caused by decades of dependence on fossil fuels, including air pollution.

For the first time in India’s history, solar power is now more affordable than coal. According to a 2018 progress report by the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE), solar capacity increased eightfold between 2014 and 2018. Furthermore, the ministry predicts that by 2022, solar power capacity will surpass the 110,000 gigawatt goal set for that year.

A 2017 report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) states that India’s coal tax, which brought in US$2.7 billion in 2015, has been integral to funding sustainable energy projects across the country that will, in the long run, alleviate air pollution produced by the coal industry.

The nation’s propensity for planting trees has grown into an impressive grassroots response to air pollution and climate change. In 2017, India set a world record when 1.5 million volunteers in Madhya Pradesh planted 66 million trees along the Narmada River in 12 hours.

However, Pardiwala says that as air quality worsens for many, apathy towards pollution is becoming as common in India as anywhere else. One of CERE’s goals is to stem such sentiments by helping people to develop a sense of agency through education and community programs.

“There is a sense that the problem is too large — so what can an individual do?” Pardiwala explains. “I think that individuals feel incapable of taking action, but they need to realise that communities need to come together. One individual may not be able to solve a problem, but if a community comes together I think we certainly can.”